Cyberattacks on operational technology (OT) were virtually unknown until five years ago, but their volume has been doubling since 2009.

This threat is distinct from IT-focused vulnerabilities that cybersecurity measures regularly address. The risk associated with OT compromise is substantial: power or cooling failures can cripple an entire facility, potentially for weeks or months.

Many organizations believe they have air-gapped (isolated from IT networks) OT systems, protecting them against external threats. The term is often used incorrectly, however, which means exploits are harder to anticipate. Data center managers need to understand the nature of the threat and their defense options to protect their critical environments.

Physical OT consequences of rising cyberattacks

OT systems are used in most critical environments. They automate power generation, water and wastewater treatment, pipeline operations, and other industrial processes. Unlike IT systems, which are inter-networked by design, these systems operate autonomously and are dedicated to the environment where they are deployed.

OT is essential to data center service delivery: this includes the technologies that control power and cooling and manage generators, uninterruptible power supplies (UPS), and other environmental systems.

Traditionally, OT has lacked robust native security, relying on air-gapping for defense. However, the integration of IT and OT has eroded OT’s segregation from the broader corporate attack surface, and threat sources are increasingly targeting OT as a vulnerable environment.

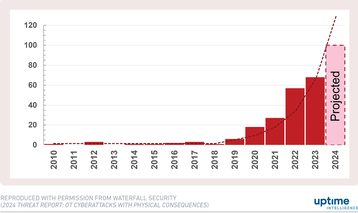

Research from Waterfall Security shows a 15-year trend in publicly reported cyberattacks that resulted in physical OT consequences. The data shows that these attacks were rare before 2019, but their incidence has risen steeply over the past five years.

This trend should concern data center professionals. OT power and cooling technologies are essential to data center operations. Most organizations can restore a compromised IT system effectively, but few (if any) can recover from a major OT outage. Unlike IT systems, OT equipment cannot be restored from backup.

Air-gapping is not air-tight

Many operators believe their OT systems are protected by air gaps: systems that are entirely isolated from external networks. True air gaps, however, are rare — and have been for decades.

Suppliers and customers have long recognized that OT data supports high-value applications, particularly in terms of remote monitoring and predictive maintenance. In large-scale industrial applications — and data centers — predictive maintenance can drive better resource utilization, uptime, and reliability. Sensor data enables firms to for example diagnose potential issues, automate replacement part orders, and schedule technicians, all of which will help to increase equipment life spans, and reduce maintenance costs and availability concerns.

In data centers, these sensing capabilities are often “baked in” to warranty and maintenance agreements. However, the data required to drive IT predictive maintenance systems comes from OT systems, and this means the data needs a route from the OT equipment to an IT network. In most cases, the data route is designed to work in one direction, from the OT environment to the IT application.

Indeed, the Uptime Institute Data Center Security Survey 2023 found that nearly half of the operators using six critical OT systems (including UPS, generators, fire systems, electrical management systems, cooling control, and physical security/access control) have enabled remote monitoring. Only 12 percent of this group, however, have enabled remote control of these systems which requires a path leading from IT back to the OT environment.

Remote control has operational benefits but increases security risk. Paths from OT to IT enable beneficial OT data use but also open the possibility of an intruder following the same route back to attack vulnerable OT environments. A bi-directional route exposes OT to IT traffic (and, potentially, to IT attackers) by design. A true air-gap (an OT environment that is not connected in any way to IT applications) is better protected than either of these alternatives, but will not support IT applications that require OT data.

Defense in depth: a possible solution?

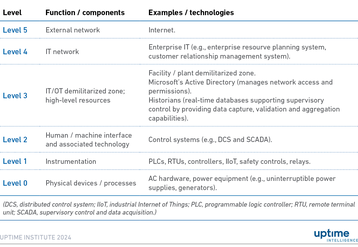

Many organizations use the Purdue Model as a framework to protect OT equipment. The Purdue Model divides the overall operating environment into six layers. Physical (mechanical) OT equipment is level 0. Level 1 refers to instrumentation directly connected to level 0 equipment. Level 2 systems manage the level 1 devices. IT/OT integration is a primary function at level 3, while levels 4 and 5 refer to IT networks, including IT systems such as enterprise resource planning systems that drive predictive maintenance. Cybersecurity typically focuses on the upper levels of the model; the lower-level OT environments typically lack security features found in IT systems.

Lateral and vertical movement challenges

When organizations report that OT equipment is air-gapped, they usually mean that the firewalls between the different layers are configured to only permit communication between adjacent layers. This prevents an intruder from moving from the upper (IT) layers to the lower (OT) levels. However, data needs to move vertically from the physical equipment to the IT applications across layers — otherwise the IT applications would not receive the required input from OT. If there are vertical paths through the model, an adversary would be able to ”pivot” an attack from one layer to the next.

This is not the type of threat that most IT security organizations expect. Enterprise cyber strategies look for ways to reduce the impact of a breach by limiting lateral movement (an adversary’s ability to move from one IT system to another, such as from a compromised endpoint device to a server or application) across the corporate network. The enterprise searches for, responds to, and remediates compromised systems and networks.

OT networks also employ the principles of detecting, responding to, and recovering from attacks. The priority of OT, however, is to prevent vertical movement and to avoid threats that can penetrate the IT/OT divide.

Key defense considerations

Data center managers should establish multiple layers of data center OT defense. The key principles include:

- Defending the conduits. Attacks propagate from the IT environment through the Purdue Model via connections between levels. Programmable firewalls are points of potential failure. Critical facilities use network engineering solutions, such as unidirectional networks and/or gateways, to prevent vertical movement.

- Maintaining cyber, mechanical, and physical protection. A data center OT security strategy combines “detect, respond, recover” capabilities, mechanical checks (e.g., governors that limit AC compressor speed or that respond to temperature or vibration), and physical security vigilance.

- Preventing OT compromise. Air-gapping is used to describe approaches that may not be effective in preventing OT compromises. Data center managers need to ensure that defensive measures will protect data center OT systems from outages that could cripple an entire facility.

- Weighing up the true cost of IT/OT integration. Business cases for applications that rely on OT data generally anticipate reduced maintenance downtime. However, the cost side of the ledger needs to extend to expenses associated with protecting OT.