The typical article on emerging big data architectures begins with a sweeping hyperbole about the tremendous shifts in the infrastructure of the back office to a completely different paradigm or way of reasoning. There’s a bit of fantasy in all of that. For the manufacturers and vendors of new technologies to survive going forward, there has to be a tremendous shift in back-office infrastructure, otherwise they’ll be stuck servicing data warehouses into eternity.

Take it from someone who’s still plowing through the complaints about Microsoft’s termination of Windows XP’s service life: There’s nothing preventing present-day data warehouse (DW) infrastructures from being extended out beyond our own natural lifetimes, let alone theirs. While vendors such as EMC speak about how “data is growing,” it really isn’t. It’s multiplying. A great deal of the efficiency of existing DW systems lies in their ability to eliminate redundancies, which is all part of the structuring of data in formal database systems. Hadoop is not a formal database system; by design, it’s an operating system and a file system for utilizing data in its unstructured, or raw, format.

Our big data is bigger than theirs

Because Hadoop made big data so useful, organizations began seriously questioning whether their existing DW deployments were as efficient and as cost effective as they could be. This put the question of change on the table, which gave a new cadre of vendors the leverage they needed to expand that question into complete and total replacement.

It’s the evolution of that question into a serious re-examination of data storage, that put the established vendors in this space — including Teradata, Oracle, and EMC — into a quandary. How much change can they embrace (read: “swallow”) while retaining their existing foothold in the data center?

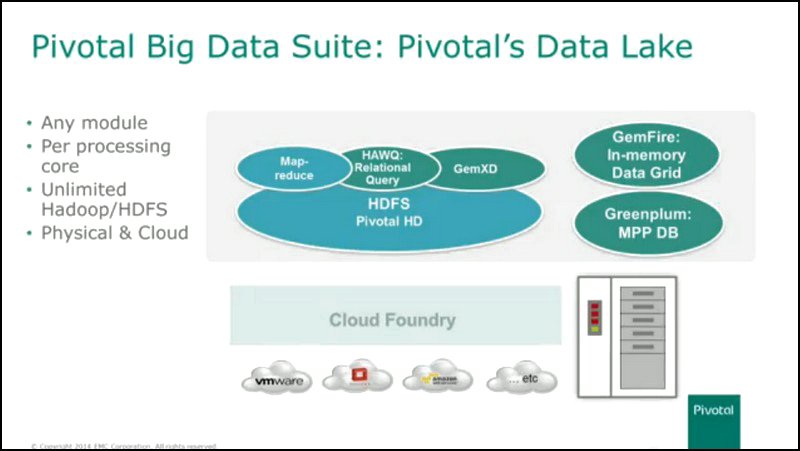

Last year, EMC’s strategy was to integrate bits and pieces of Hadoop into its established product plan. This included the release, by its Pivotal division, of a Pivotal HD platform that effectively integrated its existing Greenplum analytics appliance with Hadoop’s HDFS file system.

Tuesday morning’s announcement by EMC of its VMAX3 platform is a further concession — EMC swallowing more of the big data phenomenon, without ingesting it entirely (or, perhaps more accurately, vice versa). The goal is to keep EMC hardware in the datacenter, while at the same time acknowledging the reality that public cloud capacity will be used, both to ensure data integrity as well as provide the big workbenches that big data analytics tools require.

In a bold, but perhaps wise, acknowledgement that new data storage hardware is not enough in itself to excite CIOs into redesigning their infrastructures, EMC is betting big on an entirely new, cloud-inspired business model: In place of its old system of charging for storage capacity, EMC has begun charging for processing cores and compute transactions — for the act of moving storage into cache memory for analysis. This way, customers will be encouraged to “store everything” (a marketing catch-phrase which EMC is trying out on the public), and only pay when everything is actually being used.

Store Everything

“The idea is, we’re encouraging you to store everything,” announced Pivotal CEO Paul Maritz during last month’s EMC World conference. “We shouldn’t be taxing you for ‘dark data,’ because when you store everything, there’s probably going to be large parts of your data that you don’t know whether you’re actually going to use or not. It’s just sitting there. You may use it; you may not. We don’t want to tax you for that. We only want to tax you essentially when you pull the data up into memory and start working with it.”

The pool that contains all the data, including the so-called “dark data” to which Maritz referred, was given a metaphor by EMC last year: the data lake. It is this metaphor which EMC, Pivotal, and VMware all jointly depict as replacing the data warehouse, probably gradually, though certainly eventually.

To do this, the trio have to advance a curious new theory of operation. Whereas competitors such as Teradata are just bold enough to introduce Hadoop as a means of “landing” new or incoming data prior to its being “cleansed” and integrated into the DW, the data lake proponents depict the Hadoop File System (HDFS) as the destination zone for all data that can then be analyzed in memory using GemXD (Pivotal’s reworking of its GemFire in-memory database component for HDFS), and queried and reported on using HAWQ (Pivotal’s reworking of its Greenplum MPP DB query engine for HDFS).

It’s big data, but not as we know it

“The Hadoop movement really has two pieces,” explained Maritz. “It has this technology called HDFS which is really the open source equivalent of the Google file system... We think that HDFS is going to be the long-lasting contribution from Hadoop. Hadoop will establish HDFS as the common repository where information goes to live.”

Maritz doesn’t actually mention the other piece. There is an operating system component of Hadoop that runs math and analytics functions on widely distributed data, and VMAX3 does not “embrace” or “encompass” or “engage” any part of that. While utilizing HDFS enables Pivotal and EMC to commandeer Hadoop’s friendly yellow elephant logo in its presentations, the processing of data that swims in your lake takes place using Pivotal’s branded components.

It’s a graceful and clever way for Maritz to admit that the data lake concept at the heart of EMC’s and Pivotal’s Isilon platform is not all of Hadoop, and is not “big data” as we have come to expect it.

“There is going to be a transitional period. Today, we need the existing paradigms,” Maritz said, “and as we move to this HDFS paradigm, we want to make it easy to shift, mix, and match.” Both existing and new EMC storage hardware, coupled with the company’s new Elastic Cloud Storage appliance (essentially a pluggable flexible hybrid storage component), present what Maritz describes as the “foundation” for the new data lake platform.

That foundation, he implied, will allow legacy equipment to be useful until the end of its service lifetime, while at the same time customers can add flash storage for such things as in-memory data caches.

One more thing about Maritz’ little sleight-of-hand: HDFS may not necessarily be the de facto file system for Hadoop going forward. For instance, one player in the Hadoop space named Quantcast is touting its QFS file system as interoperable with all the other Hadoop components, while saving as much as 50% in disk space.

Pivotal’s and EMC’s response to this is literally to argue that size does not matter anymore — that you should be able to store everything, including the dark data you might not care about anyway, and not care about capacity. It’s a clever ploy, and in our next installment in DatacenterDynamics, we’ll break down the components of the VMAX3 platform in greater detail to see whether EMC’s plan to make you not care about capacity any more, has a chance of paying off.