Bitcoin began in the bedroom. Initially intrigued by a mathematical curiosity, the first miners used spare compute on personal gaming rigs to unlock worthless amounts of virtual currency.

In the following years, however, as the cost of mining grew rapidly, and the value of the coin grew even faster, it would soon leave the home. An entire cottage industry sprung up, consuming as much power as nations, relying on custom silicon to chase digital coins.

This growth mirrored a similar explosive build-out in the traditional data center sector, but was always seen as separate from the Internet’s infrastructure - a shadow data center network for a shadow financial system.

This feature appeared in Issue 55 of the DCD Magazine. Read it for free today.

Now, however, the two worlds are converging. The rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence, and its dramatic power demands, have forced companies to reconsider what they’ll accept from a data center provider, allowing historical outcasts to be remodeled as new industry titans.

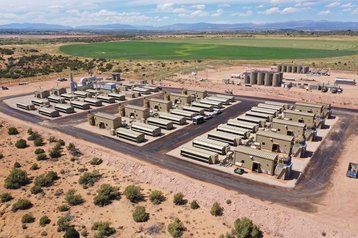

"Our company is a data center business at heart," Core Scientific's CEO Adam Sullivan says. "We have the largest operational footprint of Bitcoin mining infrastructure, and that's required traditional data center people to operate it - because no one had operated nearly a gigawatt of infrastructure in the past, and you couldn't take regular Bitcoin mining operators and put them into that role."

Core Scientific is but one of a growing number of cryptomining companies that has pivoted to serve generative AI businesses. Some, such as CoreWeave, have completely abandoned their mining roots in search of new riches, while others are still trying to straddle both worlds.

Hive Digital Technologies, Northern Data, Applied Digital, Iris Energy, Mawson Infrastructure, Crusoe, and others are but just a small number of those that have made the shift.

“We're moving very quickly into building the infrastructure that’s going to be powering the AI wave, and we've got a big pipeline of opportunities we put together,” Crusoe co-founder, president, and COO Cully Cavness tells DCD, adding that the company is aiming to deliver “gigawatts of new data center capacity.”

The company launched in 2018 as a cryptominer deploying containerized data centers to oil wells to harness natural gas that would otherwise be "flared off" and wasted.

Unlike latency-sensitive workloads or ones beholden to regulation, crypto doesn’t care where it is mined. This meant that the sector ignored most other location factors, instead giving primacy to power - focusing simply on cost and access.

AI training clusters are not too dissimilar, and as a result the data center sector is now chasing power. Inference data centers are more latency-sensitive, but the industry will still prioritize power access above all else, locating data centers in suboptimal locations simply because it’s the only place with enough near-time local grid capacity available.

“We're really doing this in an energy-first way where we're going to places that have a lot of overdeveloped or excess, otherwise curtailed, power,” Cavness says. “And sometimes these are in remote areas.

“We're taking that same ethos into the AI development space where we're going to some places that might have curtailed wind, hydro, or geothermal power. We still have some AI capacity being powered by our flared gas operations - such as in Montana, the Bakken oil field - and really just moving quickly to try to bring on as much capacity as we can.”

The company, rather unusually, also has its own power generation infrastructure. “We own and operate 230MW of natural gas-fired power generation equipment, which includes turbines and reciprocating engines,” he says.

Cavness argues that the wider industry is still trying to come around to terms with this new world. “Bitcoin mining has a pretty fast-moving, nimble, scrappy development cadence, and my sense of the way that the AI infrastructure industry is gonna move more towards that kind of rapid development and deployment,” he says.

The company in November 2024 filed with the SEC to raise $818 million, on top of hundreds of millions in previous rounds. The month before, Crusoe entered into a $3.4bn joint venture with asset manager Blue Owl Capital to build a huge data center in Abilene, Texas.

When this article was first published in the magazine in December, the Abilene site was planned to be leased to Oracle, who will then rent it to Microsoft, for use by OpenAI. Now, the site is set to be the heart of OpenAI's Stargate initiative, which plans to spend $500bn on AI data centers.

These elaborate nesting doll deals are a function of this particular moment in time, where capacity is so constrained. Microsoft has long turned to wholesale colocation partners to supplement its data center capacity, but the demand for AI and the shortage of Nvidia GPUs forced it to loosen its control even more.

The hyperscale giant signed two blockbuster deals last year, with Oracle and CoreWeave, for access to data centers and GPU infrastructure. “The Oracle deal was a big one, we had to get Satya [Nadella, Microsoft CEO] to sign it off,” one senior Microsoft executive told DCD under the condition of anonymity.

Microsoft’s investment in OpenAI also came with a condition of cloud exclusivity, but the generative AI firm has pushed for more compute and faster capacity, causing Microsoft to have to turn to its competitors to keep up - as long as its name is at the end of the chain of companies. With Stargate, that exclusivity with OpenAI has now morphed to first right of refusal for new capacity.

“It's so hard to speculate where that type of deal is going to go,” Core Scientific’s Sullivan says.

“On one side, folks like CoreWeave are forming a very sticky business. They're providing a service to these hyperscalers that they really can't find elsewhere, shifting capex to opex while being able to move at a speed that is often unmatched in the data center.

“But on the other side, at some point, will there be disintermediation? Will Microsoft get to a point where their own economics require them to start going direct to the data center developers, or will their internal data center team catch up and be able to replace all that infrastructure?”

This infrastructure, Sullivan says, is not easy to “lift and shift.” He explains: “These are hundreds and hundreds of megawatts of infrastructure that have been purpose-built for their use cases. So the big question is, given the stickiness, given the amount of investment in infrastructure, given that they already have the facility and the connectivity, will they be able to disintermediate in the future?”

Core Scientific is a part of that interconnected web of infrastructure. It operates its own crypto operations and HPC/AI business, but is also a major infrastructure provider for CoreWeave - such a large part, in fact, that the latter business unsuccessfully tried to acquire it earlier in 2024.

“We hosted them when they were an Ethereum miner, back in 2019-2022,” Sullivan recalls. “Core Scientific was one of the largest hosters of GPUs in North America, so we had a close relationship with them. They knew our capabilities; they knew our sites.”

That partnership abruptly ended when Ethereum went proof of stake, a different type of Blockchain technology requiring far fewer GPUs. “I think they were excited to move back into some of the sites where we previously had GPUs for them,” Sullivan says. “Obviously, the infrastructure looks much different for this.”

How different the infrastructure needs to be remains a point of contention. Crypto sites could often avoid much of the complexity of an enterprise endeavor, allowing them to be faster and cheaper.

Thin walls, low security, little redundancy, and rows of cheap ASIC rigs are often the hallmarks of a crypto data center - with the end result closer to a shed than critical infrastructure.

The companies that had the most ramshackle bare-bones facilities have found it the hardest to pivot, while the larger crypto companies that had more to work with have found themselves in a better position.

“If you look at our facilities and you take a look at Yahoo data centers, they look very similar,” Sullivan says, referencing the traditional ‘chicken coop’ design that was once the rage. “So we essentially stripped back what was necessary to run Bitcoin mining from that design. And now we have a number of things to add back when we convert it to HPC. But from a structural standpoint, it is a very similar design.

“We add in chillers, batteries, gensets, UPS systems, and the whole mix of things that are necessary to do a conversion to HPC.”

While this is still a lot of work and cost, Sullivan argues that other data centers are similarly facing a conversion challenge at this inflection point. “Many of the traditional data centers are having trouble converting existing data centers as they have to do full facility conversions due to the power density and the water-cooled nature of the newest generation GPUs,” he says.

Crypto operators are currently reviewing their existing footprints to see which make sense for conversion - during which time they would, of course, lose any revenues from mining. At the end of it, they’ll be left with less capacity.

“A crypto site that's 55MW on a piece of fixed land is not going to be 55MW Tier III,” says Corey Needles, managing director of Northern Data's Ardent Data Centers. “No, it's going to be half of that, if not less, for all the infrastructure and at this density that I'm going to have to put in the ground.”

The real question, however, is how much of this extra infrastructure is necessary. Security will be non-negotiable for most customers, while shifting from ASICs to GPU servers that cost as much as a house will necessitate more cleanliness, care, and temperature control.

“You have to be a lot more respectful of the AI and HPC hardware,” says Applied Digital’s CTO Mike Maniscalco. But, at the same time, he argues that there are lessons to be learned from mining’s approach to power use and redundancy.

“Within a matter of seconds to minutes, you can take a miner and go from full power consumption down to a trickle and then pick right back where we left off,” he says. “And it's beautiful. It just works really well where there's a dynamic power availability - sometimes power may be really, really cheap, so it makes sense to go full bore, but other times, it may get expensive, and it may make sense to wind down.”

For training runs, the power costs can be enormous, while adding redundant infrastructure is both costly and time-consuming. “When you talk to a lot of AI companies about how they design and engineer their training runs for resiliency, they expect some failures, bugs, OS issues, and hardware issues,” Maniscalco says.

“So what they tend to do is make checkpoints systematically throughout training runs. If the training was to fail because of a hardware or software failure, it just picks up from the last checkpoint.”

This, Maniscalco says, “theoretically gives you the ability to wind down power quickly and pick up from the last checkpoint once that power is restored.” He continues: “All you've lost is a small amount of training time, in theory. We really like that mindset of how you can change the power delivery and design to reduce costs to get things to market faster to save a lot of money on generator purchasing.”

The market is still experimenting with the right way, “because they're very conditioned to having full redundancy,” Maniscalco adds. However, in a stark reminder of the importance of redundancy, Applied itself posted a loss in early 2024 after faulty transformers caused a lengthy outage at its North Dakota data center.

Most likely, Core Scientific’s Sullivan predicts, is for the sector to adopt a mixture of redundancies.

“We're seeing a lot more multi-tier being developed for GPU clusters,” he says. “If you take the traditional Tier III model, you might be spending $10 to 12 million a megawatt. You can come in a few million per megawatt below that number for standards that the customers are completely fine with.

“They understand that there are points in time where, if it's absolutely necessary, they can go back one or two minutes in terms of where the model was. That's worthwhile.”

Another area he sees convergence between the two sectors is AI “moving into the world of ASICs,” that is, specialized AI hardware instead of the more general GPUs. “I think we're going to start to see much more commoditized compute, similar to what we saw in Bitcoin mining.”

OpenAI is believed to have contracted Broadcom to help it build its own ASICs for 2026, but whether they will be able to compete with GPUs (especially for training) is unclear.

It’s also unclear what the future holds for both crypto and AI. The launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 is generally seen as the start of the current generative AI race.

At the time, a single Bitcoin cost some $17,000. For most of 2024, it hovered around $50-60,000. The election of Donald Trump sent it soaring to record heights however, with the virtual currency just shy of $100,000 at time of publication.

A promise of looser regulations, a national Bitcoin reserve, and economic uncertainty all seem to suggest continued high valuations.

"It has not changed our philosophy at all," Sullivan says. "Even with the more recent significant increase in the price of Bitcoin, mining economics are still very challenging."

Power costs remain a constraint, and show no sign of improving. At the same time, the ability to mine crypto has commoditized, making it harder for first movers to stay ahead. "And so that edge that you had is getting eked away," Sullivan said, although the company plans to continue its crypto business as its AI one builds.

Others DCD spoke to pointed to the challenge of serving a sector with wild price swings to create a digital coin with no intrinsic value. Similar things could be said about generative AI, which has yet to prove a sustainable business model, and is built on the promise of vast technological advances that are yet to come.

"You can really mitigate that risk through the credit quality of the tenants that we're building around," Crusoe's Cavness says. "So if we're taking a large, long term, that requires building a data center and a permanent location, multibillion-dollar investment, that needs to be tied to a high credit quality lease, that ultimately there's a guarantee that that's going to be paid."

Sullivan, similarly, says that Core Scientific is "focused on long-term contracts, some that are more than 12 years."

The challenge is, however, that in a speculative gold rush, only some of those building data centers actually have an anchor client.

"The part that does worry me is the amount of people that are building purely on spec right now that are going to be delivered four years from now, like 2028," Sullivan says.

"The industry could face some headwinds where we start to see some cracks in terms of demand, in terms of people being able to find clients, actually fill all that space, given the amount of capital being put into this industry right now. That is a major concern. Is the level of investment that is going to match where the demand falls?"

An interrelated concern is "the amount of debt that's being taken on to purchase the GPUs, it is probably one of the more worrisome aspects of the growth of this industry," he says.

For the AI sector, this may prove the final and most painful lesson to be learned from the crypto miners: During Bitcoin or Ethereum price crashes, the market has swept away those that timed it wrong, and were left holding debt when demand evaporated.

As both former miners and former traditionalists chase the same AI workloads, they will face a precarious gamble, one that could end in riches or disaster. Operators will be forced to ask the same question that has long plagued the Bitcoin sector: Can the line keep going up?