If your business wants a connection in Africa, India, or the Far East, you might find yourself looking at a platform originally founded as a very local service handling Internet traffic in Germany.

The story of how DE-CIX changed from a single-country Internet exchange to a global interconnection player is the story of big changes in networking - and in the way society consumes those networks.

The Internet was created in the United States. By the early 1990s, it had grown internationally, linking networks round the world. But all peering still took place in the United States, so when two Internet users on different networks communicated, all their traffic still had to go through the US.

This applied in every country in the world, creating heavy delays, and massive network costs in days when international bandwidth was much more limited and expensive than it is today.

Two users connecting in London or Frankfurt had to effectively communicate over a two-way link to the only Internet exchange points, with all their traffic going to the US and back, adding massive delays and telecoms costs.

Starting in a post office

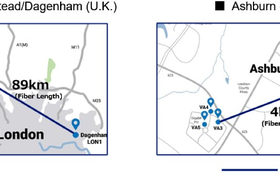

Local groups could see an answer. In late 1994, a group of five British Internet service providers (ISPs) set up the London Internet Exchange (LINX), using a Cisco Catalyst switch with eight 10Mbps ports in London’s Docklands.

In 1995, Germany followed suit swiftly, with its own Internet exchange point (IXP), the Deutsche Commercial Internet Exchange (DE-CIX).

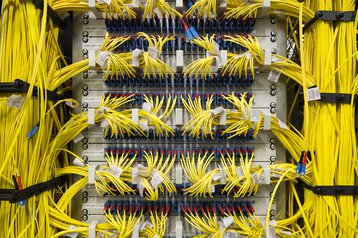

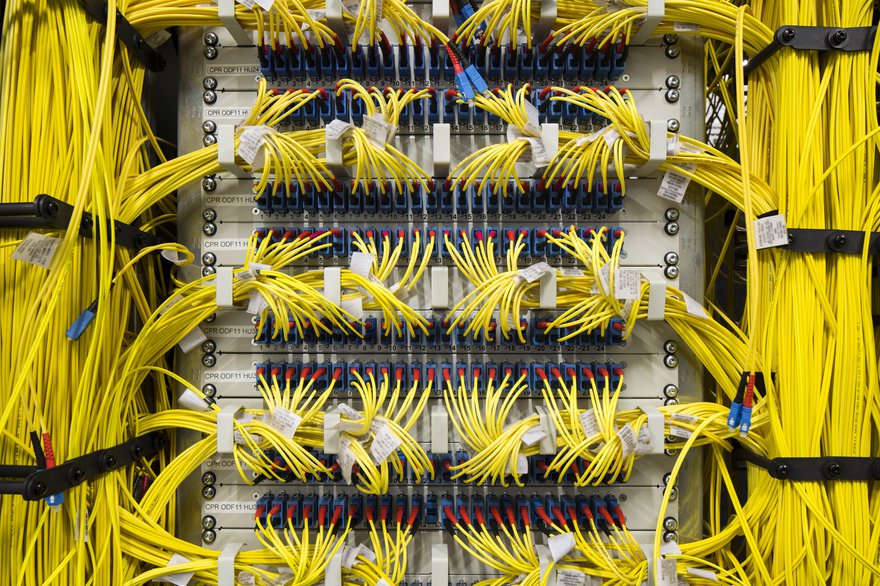

Internet exchanges in all countries have grown massively: DE-CIX for instance now connects more than 3,000 networks.

“In 1995, DE-CIX was established as a pure peering point, a fabric operator,” says Ivo Ivanov, DE-CIX’s CEO.

Three ISPs launched the German IXP in the back room of a post office in Frankfurt, and expanded into an Interxion data center, becoming one of the largest Internet exchanges in Europe.

“Over time we grew in Frankfurt, and we added Hamburg and Munich,” he says. “In 2007, Telegeography said we were a new telecommunications capital of Europe, because of the huge concentration of traffic between the Western and Eastern hemispheres.”

That’s when DE-CIX realized it had an international opportunity. If you’ve created a distributed carrier-neutral exchange platform in multiple data centers in one metro area, then you can do it in others.

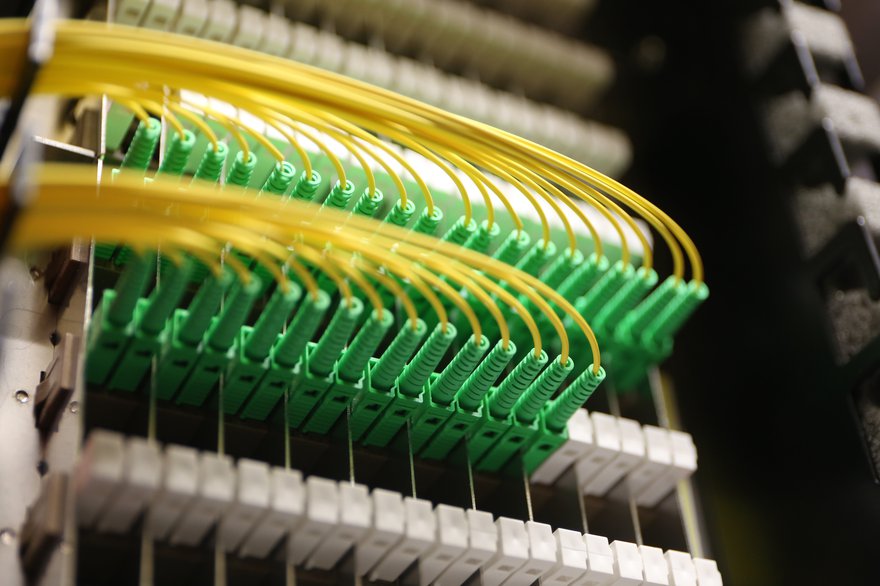

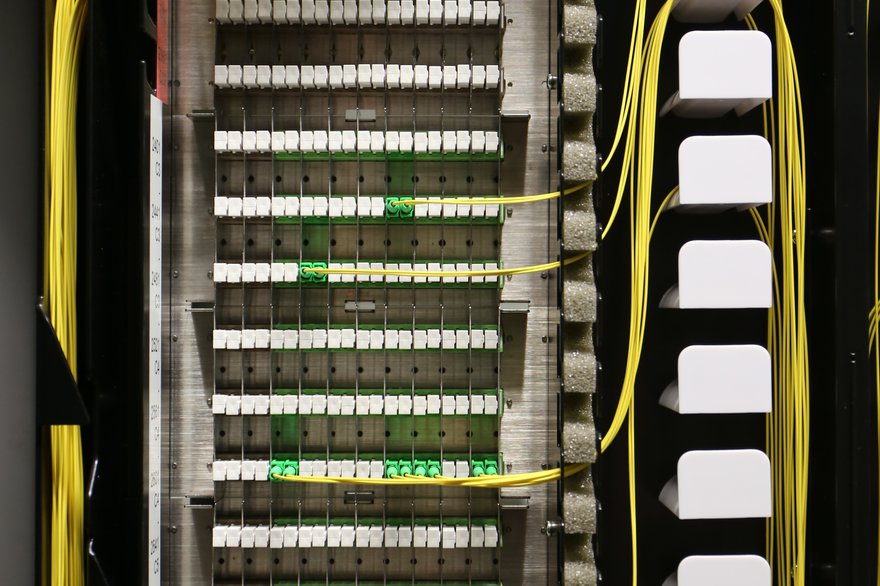

“A data center- and carrier-neutral, distributed platform present in a metro in different data centers, all interconnected into one integrated fabric, is great from the redundancy point of view, and from the distribution point of view, with a very high level of accessibility.”

The nature of an IXP began to look more like a business model than a simple network exchange, he says: “Potential participants can join the fabric regardless of which data center they're physically located in. It's a matter of cross-connects only.”

That’s pretty similar to the Equinix International Business Exchange (IBX) model, he says, but with one big difference: “They [Equinix] offer their fabric to their own customers only.”

“Our success in Frankfurt gave us the confidence to export this type of know-how, this experience on the engineering and business development side, to other regions.”

DE-CIX looked for regions that lacked this type of infrastructure or ecosystem, where there was no localization of content and data gravity. Its first target was Dubai.

‘UAE-IX powered by DE-CIX’ was launched with local telco Datamena in 2012. Since then, it’s become an international and regional hub, and Ivanov reckons the presence of DE-CIX was “one of the main factors” contributing to Dubai’s ascendence in digital commerce in the Middle East.

“To create an attractive framework for operators who are not from the region, the regulatory authority created the so-called free interconnection zone based on our guidance.”

Global networks are changing

With that success, DE-CIX next went into areas that already had infrastructure, but wanted to consume networks differently. The German outfit set up exchanges in the US cities of New York, Dallas, Chicago, Richmond, and Phoenix.

Alongside that, there are now European exchanges in Marseille, Palermo, Lisbon, and Barcelona, with another serving the Turkish market in Istanbul. Five years back, an exchange was established in Mumbai, with other hubs following in Delhi, Kolkata, and Chennai.

DE-CIX’s Indian operation claims to be the largest interconnection platform based on the numbers of participants in Asia, Ivanov says.

Southeast Asia followed with IXPs in Malaysia, and Singapore. There’s a partnership announced with the Getafix exchange in the Philippines - and a move to offer exchange services across the whole of Africa.

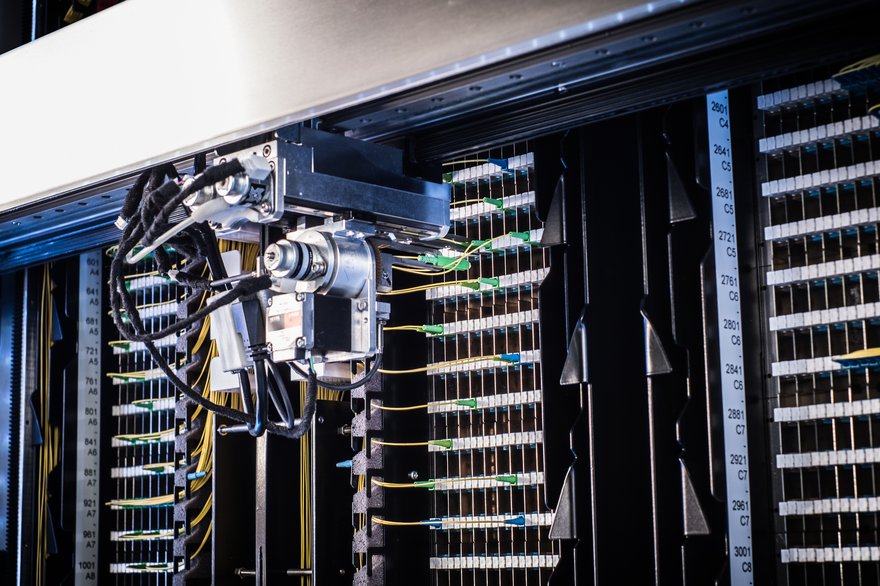

The African service takes a new network approach, matching a more consumer-centric network market. It’s a managed solution that Ivanov calls “DE-CIX-as-a-service” or ‘interconnection fabric in a box.’

“We deliver a turnkey full-fledged interconnection fabric with hardware, software, and processes - but also including marketing and business development activities,” he says. “It's literally the full cycle needed to run a successful interconnection fabric and create an ecosystem.”

Coming back to the comparison with Equinix, he says: “When I’m asked 'what's the difference between DE-CIX and Equinix?' I say 'we have more data centers.'"

Of course, DE-CIX doesn’t own data centers, he explains: “We do not have data center operations. We collaborate with the data center operators. We have more data centers enabled. We are in more than 700 facilities around the globe. Including Equinix.”

The service has expanded up the stack as well, offering cloud connectivity over and above network peering, with a so-called “multi-service access port,” that can support what DE-CIX calls a “cloud router,” designed to let customers hook together multi-cloud networks.

That means DE-CIX can offer a network security service, giving a direct Layer 2 network connection into cloud services such as Microsoft applications like Azure, Office 365, CRM, and ERP.

Enterprises are network operators now

These services are aimed at a different set of customers from the traditional ISPs and network providers linking to an Internet exchange port. They are picked up by large enterprises in multiple industries.

“We see a huge wave of new market participants on platforms like DE-CIX, who are probably not interested in peering directly,” he says. “They're interested in cloud connectivity.”

All the big industries are getting involved in direct management of their connectivity, says Ivanov. “And the bigger they are, the higher the demand for global network presence.”

For instance, he says, eight years ago Netflix and Apple didn’t own a single Point of Presence (PoP). “They were not connected to even one Internet Exchange. Today. Netflix and Apple have hundreds of PoPs in hundreds of different exchanges around the globe.

“They're still huge enterprises,” he says. “But today they are also a global network operator. They run their own global network for resilience, for cost saving, but even more importantly to control the data journey to their customers.”

Ivanov thinks that banks and automotive companies will be the next big global network operators: “We know from different projects which have been announced that finance institutions have started investing in their own subsea cables, and automotive companies are building their own mobile networks. If you control the data journey, you control the gateway, and you can control the gateway only if you are directly involved in infrastructure.”

What these customers want is virtual private networks - and that’s something a peering platform can offer, by setting up a closed user group. This means, for instance, that an auto firm can keep tabs on all the data that flows in and out of a connected car.

“The closed user group approach gives them a private virtual ecosystem for direct interconnection, which is more isolated, more secure and in specific compliance with regulatory requirements.”

Peering at the Edge

The neutral exchange approach also lends itself to Edge services, he says: “As we all know, all the applications which are extremely important today, and will evolve even further in the future, have one thing in common - they're extremely performance sensitive. That means they are latency sensitive. Every single millisecond counts.”

He goes on: “All the crucial processes in a company are somehow related to real time communication, and latency is an extremely important factor. I love to say latency is the new currency in our industry.”

As-a-service exchanges can be set up anywhere, he says: “We’re creating new telecommunications hubs in the Edge, in tier two and tier three. We have projects for creating Edge interconnection setups on highway crossroads or next to a mobile cell tower.”

As with the large facilities, DE-CIX isn’t making its own Edge facilities. It’s placing a “pizza-box” of its own kit into the appropriate Edge modules - or any other configuration up to four cabinets in a Tier One hub.

In the US, DE-CIX is working with Edge players like DartPoints, while Ivanov says some interesting options are emerging: “AtlasEdge is an interesting one in Europe, and I believe companies like EdgeConnect have started looking into a related approach - so I think the landscape will be very interesting.”

The joy of duplication

With a lot of players offering access to Edge networks at different layers of the network stack, there are bound to be overlaps, Ivanov concedes, but actually this can be a good thing.

In terms of network peering, there are other players offering software-defined networking (SDN) services, such as Megaport, Packet Fabric, and Console Connect. But he’s happy to collaborate with them to extend the reach of both services, and he argues that overlapping services are complementary, and can reduce the inherent risk of moving to one cloud provider.

“This overlap means there are redundant solutions for the market. Enterprises do not want to rely on only one fabric, and the bigger they are the higher the need for redundancy so they can be extremely solid in the case of an outage.”

This sort of redundancy might even be required by regulators which are starting to require financial sector organizations to have a plan to mitigate the risks of cloud concentration.

These regulations will require organizations to have a multi-cloud strategy to avoid relying on one single cloud service provider, he says: “But it also means ideally that you physically connect to different cloud zones and to different cloud connectivity solutions as well, for redundancy.”

It’s another example of an opportunity emerging from the combination of economic reality and network technology. In the end, it’s the basic changes in the way we use networks that have turned one German peering organization into a global network platform.