US President Donald Trump’s wide-ranging “liberation day” tariffs have sent global financial markets into turmoil and could have a profound impact on the data center industry.

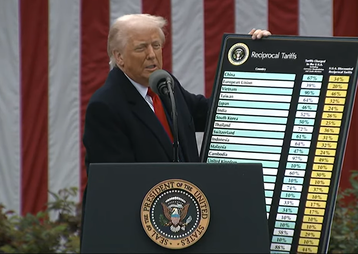

The new sanctions, announced by Trump at a press conference on Wednesday, April 2, and due to come into force this weekend, will see a baseline tariff of 10 percent placed on imported goods coming into the US. While some countries, such as the UK, will only be hit with the basic level of tax, others - described by Trump as “the worst offenders” - are facing much higher tariffs.

Trump claims the moves are in response to tariffs imposed on US products being sold abroad. “We will charge them approximately half of what they are and have been charging us,” he said on Wednesday. He added that the levels of tax represented half of the combined rate of all “tariffs, non-monetary barriers, and other forms of cheating” imposed on US exporters.

While Trump has a track record of making announcements like this and then rowing back, the threat of the tariffs has been enough to send the share prices of US companies tumbling. The value of the Dow Jones fell 2.5 percent on Thursday morning, while the Nasdaq market’s combined value fell 3.4 percent.

Tariffs are paid by the importer and not the exporter.

Chip industry gets a reprieve. For now

Trump has imposed harsh tariffs on several countries in the Far East which could have a significant impact on the semiconductor industry and the AI data center build-out in the US.

Taiwan, home of TSMC, the company that manufactures Nvidia’s GPUs and most of the other advanced chips used in servers, is facing tariffs of 32 percent, though the White House said semiconductors will be exempt from this - presumably because the US president has said dedicated tariffs for the chip industry, of 25 percent or higher, will be coming at a later date, though he has yet to provide details of how these will work.

TSMC, which has pledged to spend $100 billion on chip manufacturing in the US, has previously been told by the President that it will be exempt from levies as a result of its investment.

In response to Trump’s announcement, the Taiwanese government described the planned tariffs as “unreasonable,” and said it would seek talks with Washington.

It is less clear how the semiconductor exemption will apply to Malaysia and Vietnam. Both countries play a key role in electronics manufacturing, as well as chip packaging and testing, but do not produce finished chips in great quantities themselves. Malaysia is facing tariffs of 24 percent, while Vietnam’s rate is a whopping 46 percent. South Korea, home of leading memory chip makers Samsung and SK Hynix, is facing a 25 percent tariff.

Data center materials constraints?

A more pressing concern for data center developers could be the availability of building materials such as steel and aluminum, both of which are vital to new projects.

The US imports a quarter of its steel, with Canada and Mexico, the first and third biggest suppliers of the metal to American companies respectively, already facing 25 percent tariffs that were announced by Trump in February. These tariffs remain unchanged after yesterday’s announcement.

Brazil is the second largest producer of steel for the US market, and is facing a 10 percent levy. Lawmakers in Brazil have passed legislation that could enable it to impose retaliatory tariffs on US imports, with the government telling Reuters the 10 percent levy did not "reflect reality" and stating that the US had recorded "recurrent and significant trade surpluses in goods and services with Brazil."

Meanwhile, the US also relies on significant steel imports from South Korea, Vietnam, and Japan, which is facing tariffs of 24 percent, and Germany and the Netherlands, both of which come under the 20 percent blanket levy imposed on European Union countries.

When it comes to aluminum, America is even more reliant on imports, with more than 50 percent of its supply coming from abroad, mainly from Canada, but also from countries such as Australia, which is facing up to tariffs of 10 percent.

Tariffs complicate AI hardware supply chains

The prevailing rumor in Washington had been of a 20 percent tariff base rate, says Emily Benson, a former senior advisor at the US Department of Commerce who is now head of strategy at Minerva Technology Policy Advisors. But she says that though the reality is lower than expected, the differing tariff rates for countries had “blown a lot of assumptions out of the water," and that the cumulative impact of new and existing levies is likely to extend beyond 20 percent for most nations.

Predicting the impact of the tariffs across the data center sector is difficult without knowing the precise makeup of a company’s supply chain, she explains. “It’s hard to get concrete information about the level of stockpiling that has gone on,” she says. “A lot of companies will have seen the writing on the wall and might have, for example, bought enough copper wire to last two years to try and get a competitive advantage.

“Before Christmas we saw a big uptick of imports into the US, which reflected some front loading and fears about tariffs.”

While the hyperscalers can afford to take steps to shore up their supply chains, smaller data center firms are unlikely to have the financial muscle or physical space to hold large amounts of components, Benson says.

In the longer term, even the big players are likely to face significant disruption in their supply chains when it comes to sourcing AI components, she adds. This is because the pool of components made in America is limited, meaning prices are likely to rise whether they opt for home-grown products or buy from abroad.

“The companies are all going to be demanding similar products and have a ton of extra cash to play with,” Benson says. “That will create inflationary pressure because they are going to be competing for a limited amount of components that are available to buy.”

Niccolò Lombatti, a TMT digital infrastructure analyst at BMI, agrees that any rush to secure key components could “create great capex inefficiencies for the construction of new data centers,” as well as for expansion activities like adding new data halls.

Some server makers have already warned of the impact of tariffs on their business. Speaking on the company’s most recent earnings call, Dell said it expected prices to rise as its costs go up. "We built an industry-leading supply chain that's globally diverse, agile, resilient that helps us minimize the impacts of trade regulations, tariffs to our customers and shareholders," said Jeff Clarke, Dell’s COO.

But he warned: "Whatever tariff we cannot mitigate, we view that as an input cost and as our input costs go up, it may require us to adjust prices. That's what we've done in the past. I can't imagine we're going to do anything differently."

An uncertain future

BMI’s Lombatti says it is inevitable that tariffs “will bring some degree of downside risk to the data center industry.” This risk is “further amplified by the threat of retaliatory tariffs in the future or a global trade war escalation,” he says.

When it comes to the myriad large data centers currently under construction in the US and beyond, projects in the planning or pre-construction phase are likely to hardest hit, Lombatti argues, because this is the stage where “procurement of inputs happens in bulk.”

He adds: “We expect higher project costs, with some data centers planned for construction that may have to scale back on size, density and potentially intended use case altogether.”

Benson also believes that plans could stall as a result of the tariffs and the potential for retaliatory measures from other countries.

She says: “There’s no clear end date for these tariffs, and that is a challenge for AI and data center companies - do they wait six weeks, or six months, to make investment decisions in case the situation changes? That could be a big problem because there’s such a lot of uncertainty.”