The Edge is all about pushing hardware and workloads out to where the data is being collected – often in remote locations with little connectivity back to the core data center.

Satellites – including the many new services being delivered from low Earth orbit (LEO) – have long been used to transmit data long distances from remote areas.

While the LEO upstarts, such as SpaceX’s Starlink and Amazon’s Kuiper, are looking to target these enterprise use cases, they are coming up against incumbents well-used to providing carrier-grade connectivity in higher orbits and looking to adapt amid changing times in space operations.

Satellite services didn’t spring fully formed from the laboratories of Big Tech firms overnight. They’ve been ably built and operated by specialized companies for decades.

Telesat, based in Ottawa, Canada, is one such operator.

Founded in 1969, it built, orbited, and operated some of the world’s first geostationary satellites in the 1970s and 1980s, though the primacy of geostationary has lost momentum more recently. Now the company is looking to enter the LEO space, offering services to Edge and government customers.

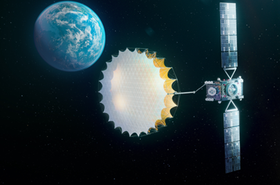

Orbiting closer to the planet at a smaller form factor, LEO satellites offer faster speeds and clearer imaging, which has drawn a lot of industry hype in recent years.

Telesat’s own entrant into low-Earth space, the Lightspeed constellation, was announced in 2016; when completed, it’s due to comprise 198 satellites in polar and inclined orbits commencing launch via SpaceX rockets in 2026 at a 1,000 km altitude. The company believes it will be cost-effective compared to fiber and microwave alternatives, and the units themselves will possess Edge data processing for modulation, demodulation, and routing in space.

Lightspeed progress

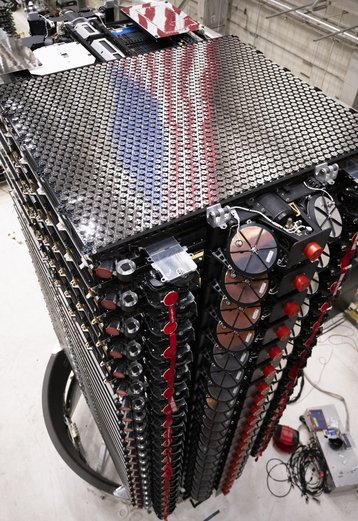

Telesat originally contracted FrenchItalian satellite manufacturer Thales Alenia Space to build Lightspeed, but pivoted to another vendor, MDA, after suffering production delays.

The MDA designs are 75 percent smaller than Thales Alenia’s, at just 750kg, but claim the same performance standards. The constellation will have 10Tbps in total capacity with four 10Gbps optical inter-satellite links interconnecting the satellites, with over 1Gbps across user terminals.

Telesat’s contract with MDA also features options for the production of an additional 100 satellites for a potential 298-strong constellation, which was the number Telesat originally planned in 2020. This was due to provide 15Tbps of capacity with commercial services starting in 2021, but the project was downsized after Thales Alenia Space reportedly saw its supply chains interrupted during the pandemic.

By contrast, MDA’s CEO Mike Greenley claimed the company could produce two satellites a day after “getting up to speed” in August 2023.

That month, Telesat announced it had aligned all its funding from the Government of Canada, and hired MDA as its prime contractor. Since then Telesat has conducted its system requirements and system readiness review and hired close to 250 new people, mostly engineers.

“We are now finalizing our preliminary design review for our global ground segment including user terminals,” Glenn Katz, Telesat chief commercial officer, says. “Then in August [2024] in partnership with MDA, we’ll have our satellite preliminary design review. After that, we’ll be jumping fully into building and eventually launching.”

The company intends to scale its commercial staff by the middle of 2025 and produce satellites for initial testing in mid-2026. By the end of 2027, the company will have enough satellites to make commercial services available.

“We’ll probably spend over a billion dollars this year in capex and opex for the project,” Katz says. “You can break that down by Lightspeed’s design, which has been eight years in the making, accommodations for the ground segment, the user terminals, and the satellites themselves.”

By the end of 2024, the company hopes to announce some significant commercial agreements with strategic partners.

LEO support for Edge

In addition to providing in-space satellite computation, LEO constellations play another key role in establishing and assuring Edge capabilities.

“To handle modern demands, users in many industries need to embrace what we call collaborative Edge,” Katz explains. “This is where your operations are backed up by a network beyond fiber to guarantee resiliency or expand operations with satellite to enable a mesh network.”

While the expansive reach of satellites often suggests it’s meant for remote industry and moving assets, Katz insisted networked backup connectivity in low-Earth space supporting the collaborative Edge could serve operations in cities, assisting mission-critical public services. He believes Edge solutions will only become more ubiquitous and necessary as global digitization continues.

"The amounts of data that connectivity users use now has become enormous,” Katz says. “Edge computing is moving away from a novel idea into a necessary part of dealing with the kinds of high volumes that have become the norm.

“Once companies in the LEO market enable lower latency, which is very important when it comes to Edge computing, you’ll see a gigantic market open up – roughly $650 billion in the 2030s [across all of LEO].”

Key industries for Telesat can be broken down into four major verticals: Enterprise, aviation, maritime (including energy and mining), and government, which in turn can be disseminated into 15-17 subverticals, Katz explains.

At sea, automation is especially crucial.

“A best-effort Internet connection just doesn’t cut it for connecting onshore Edge to these ships,” Katz says. “You’ve got to have a direct, resilient, diverse set of connections. Of course, this also applies to the smart ports we’re starting to hear more about too.”

Transport on land has similar connectivity concerns. The IoT functions of vehicle video, especially autonomous vehicles, need connection assurance.

“When you apply computational Edge to [autonomous vehicles], it’s all about minimizing delay of real-time video to local Edge centers,” Katz says. “But none of it works if you can’t guarantee strong latency. We see that as a gigantic application [for LEO satellite connectivity].”

Big tech strategies

Telesat is eager to differentiate itself from Starlink and Kuiper, which Katz identifies as being motivated to connect directly to consumers.

“Our north star is our direction as a business-to-business telco-grade service, great for mobile network operators, governments, service and cloud providers, and so on,” he says.

While Starlink’s early marketing pushes communicated it to be a broadband service, its explosive growth after entering commercial service in 2021 has since featured a number of business contracts, many of which were agreed by resellers using Starlink coverage to sell via their legacy commercial relationships.

Throughout 2023, Elon Musk’s company announced reselling arrangements to industry through SES Cruise mPOWERED, KVH Industries, netTALK Maritime, Singtel, Tototheo Maritime, Orien Reederei, and Marlink, to name a few.

But Starlink antennas are “half-duplex,” Katz says – unable to transmit and receive simultaneously. “That doesn’t work very well for Edge-type connectivity, which would prefer fiber for guarantees of latency and bandwidth as well as transmit and receive,” he explains. “We’re on the other side of the equation. We are an extension of a telco-style carrier Ethernet network at layer two.”

Starlink’s subscriber base was most recently calculated in May 2024 to be more than three million strong, with the company stating it expected to generate $15 billion in sales over 2024. Satellite market research group Quilty Space drew more conservative conclusions in May, projecting revenues of $6.6bn.

Satellite market research group Northern Sky Research (NSR) has suggested Amazon’s Kuiper could be an even greater market threat. Kuiper intends to populate a constellation of 3,236 LEO satellites, seeking to contend with Starlink’s rapid market absorption of market share.

While Kuiper is a little behind in actually getting to space, the company has its own deals under its belt. Vodafone, NTT Docomo in Japan, and Vrio in Latin America have already contracted with further sales efforts underway.

As with Starlink, the global nature of Kuiper’s offering has not been lost on its commercial team, who are looking well beyond the US for growth.

The extensive efforts to integrate the constellation’s performance with AWS, Amazon’s cloud platform, presents firmer Edge use cases than Starlink can. AWS software like SiteWise Edge, Athena, and Quicksight are already respected data tools likely to offer synergies with Kuiper connectivity, if not exclusivity.

On October 6, 2023, two prototype Kuiper satellites (Kuipersat-1 and 2) were carried to low-Earth orbit for testing as part of the “protoflight” mission. In May 2024, protoflight continued, demonstrating satellite propulsion tests, which will continue over the ensuing months to demonstrate additional maneuvers which will eventually cause enough drag to naturally deorbit both satellites via destructive re-entry.

“Starlink’s first-mover advantage allows it to set the pace and tone of pricing, period,” stated Brad Grady, research director at NSR at World Satellite Business Week in Paris in 2023. “They’re in the driver’s seat right now. Even though Kuiper is launching — it’s going to take them a while to get online and produce tangible market influence.”

The hype around LEO seeded by Starlink could never have been achieved by the legacy satellite operators, Telesat’s Katz argues.

“Kuiper is only going to extend that,” he says. “This heightened interest doesn’t mean new customers are only going to consider these two players as they become convinced about LEO adoption. The market is so big that we’re wellplaced to build a strong technological focus serving enterprise, aviation, and maritime with specific services geared to our customers. Telesat would be very happy to surf the wake of Starlink and Kuiper.”

In a report published 2023, NSR estimated that the combined Starlink and Kuiper subscriber base could become some 36 million by 2030. No matter the confidence of legacy providers, now’s the time for them to reinforce their tried-and-true reputations in the wake of saturation by deep-pocketed big tech newcomers.

While some may fight to compete, others could well be fighting to justify higher sale prices when they are sold into the new monopoly of whoever wins the Newspace race in LEO.

Sovereign LEO

A less understood trend emerging in LEO is strategic satellite capability that national security can deem “sovereign.” This refers to services procured by an end-user and developer-operator within the same country.

Anxieties over digital sovereignty heightened following the US government’s decision in 2019 to ban Chinese vendor Huawei, citing national security concerns. Several other countries followed suit, with the UK government deciding to remove all Huawei equipment from its 5G network by 2027.

With governments looking to homegrown solutions, Telesat is well-placed to serve the sovereign needs of the Canadian government, which is a big investor in the company and represents a natural procurer of its services. But the concept has more nuance to it than governments simply onshoring their technological supply chain, Katz suggests.

“Lightspeed has a capability to hand off full control of our satellites and network to a country,” he says. “We’ve been having preliminary discussions with customers around the world interested in securing that application.”

The assurance of sovereign communications is becoming a “must-have” for states, which has driven the uptake of polar satellites, Katz explains. Traditionally, the commercial utility of polar coverage is very limited beyond the needs of intelligence services and the military.

“From our own end of the fence, we see Nato treating this very seriously,” Katz says. “We believe this market is undersized today because global governments haven’t yet recognized what they want and how it works, but these discussions are happening today. One day, this technology will become one of our bigger markets."